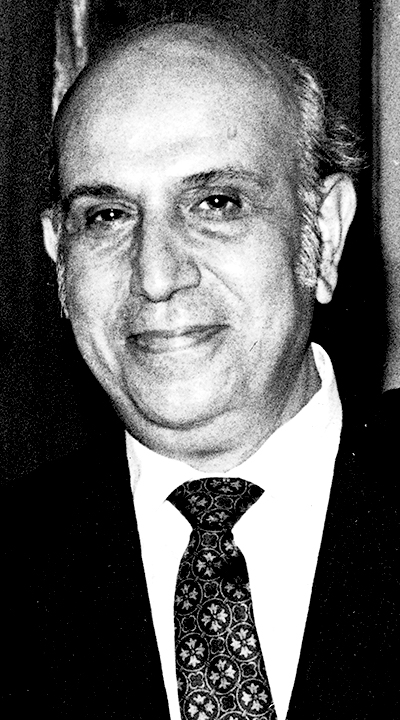

Less fashionable than Onassis or Niarchos, Costas M. Lemos was nevertheless considered one of the ‘Golden Greeks’ of the post-World War Two shipping boom. Perhaps because he was a modest and unassuming man and few details were ever known about the true extent of the empire he built, he seemed to attract speculation and nicknames. One was ‘The King of Cash’, another ‘Goldfinger’.

He had the reputation among contemporaries of being a genius and in a number of respects he outstripped his more publicly known contemporaries. Born into the foremost maritime family of the tiny island of Oinousses, near to Chios Lemos was famous as a young boy for how hard he studied. The Lemos clan was already well-established in shipping in the 19th century and his father, Michael, was himself a successful businessman who owned a small fleet of steamships and was among the founders of the Piraeus Shipping Bank.

Costas M. Lemos studied law, but he read widely, becoming knowledgeable about a wide variety of subjects. He graduated from the law faculty of Athens University, and then went to work at sea on a Lemos family vessel. Within four years he had attained his master’s papers and had a background of preparation for launching his own career in shipping.

This really began in London where in 1937 he founded Lyras and Lemos with cousins Markos and Costas Lyras. After the outbreak of the Second World War he based himself in New York where he assisted Manuel Kulukundis in management of a fleet of 15 Liberty ships that expatriate Greeks were operating in the service of the Allied cause. In effect, he was the New York Greek Shipowners’ Committee’s general manager. Throughout his career, he would make time to maintain a consistent involvement in industry committees and institutions, including three decades on the board of the Union of Greek Shipowners. The Lemos family had lost three steamships during the war, qualifying him to purchase one of the Liberty ships alloted to Greek buyers after the end of the war. This was the John Drew, built in 1943, which was renamed Michael, after his father. By the time he took delivery of the vessel in January 1947, he had already established the C. M. Lemos company in London which would be the operation’s headquarters. For the next decade he gradually expanded his fleet of Liberty vessels but, almost better than anyone else, he saw the numerous possibilities for shipping during the post-war boom.

By the late 1950s, he had already ordered his first ore-bulk-oil carriers and ore-oil carriers, a revolutionary design combining tanker and dry bulk vessel. Although some experimentation had been carried out with the combination carrier idea prior to this, Lemos will forever be remembered as one of the pioneers of this ship type.

Lemos was passionate about science and technology, as well as having an avid interest in the arts, politics and philosophy. Through his career he sought better technological solutions for the vessels he would build. He also employed a high-calibre team of people around him. C. M. Lemos is credited with introducing horizontal bulkheads for its combination carriers to improve cargo capacity and stability. He is also said to have been the first major Greek shipowner to build the bigger bulk vessels of the time with the bridge at the stern, rather than amidships, as was the prevailing trend.

He was among the first to place orders with Japanese shipbuilders in the 1950s and such was the volume of work he gave to that country’s yards that in 1965 he was honoured by Japan for his contribution to its economic development.

Commercially, Lemos was extremely smart. He enjoyed long term contracts of affreightment for major cargo owners such as US Steel. He was able, for example, to improve the rate his company was paid per ton of cargo by offering to perform the contract in fewer voyages with larger vessels coming out of the shipyards. This defied the normal logic of economies of scale. His combination carriers could carry oil from the Persian Gulf to Brazil and then iron ore from South America to the Far East in volumes that comparatively rivalled the giants of today’s ore trade.

In the mid-1960s, he was already experimenting with an ore-bulk-oil carrier of 70,000-tons with a double-shell at Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries (IHI). That was 20 years before the first double-hull tankers would be ordered by a Greek company. In 1971, he received the 174,000-ton OBOs Rhetoric and Romantic from Nippon Kokan, the world’s biggest bulk carriers. Meanwhile very large crude carriers were rolling off the production line at the A. G. Weser shipyard in Germany. By the start of the 1980s, he had overtaken flamboyant rivals and controlled a fleet of more than 2 million tons carrying capacity, the largest of any Greek shipowner. In the next five years, he dramatically downsized the fleet. Some ships were sold before the worst of the shipping crisis of the early 1980s, decisively reducing the damage sustained by the operation, although some vessels were sold in the middle of the shipping recession. By 1986 the C. M. Lemos fleet was reduced to just five vessels.

His interests and even his business horizons were far wider than shipping. He had considerable holdings internationally in real estate and stocks, and he was reputed to be a major shareholder in several American banks. But the empire was so vast and so low-key that even insiders were never sure of the scope of it. Lemos himself, however, seemed to have everything under control.

Apart from being highly astute both financially and technically, he never lost sight of the human element in shipping, or life generally. He was a major contributor to maritime education in Greece and believed that being a seafaring nation was the secret to the country’s rise in the shipping business. Like many of the causes he supported, donations went mostly unadvertised.

Lemos did not surround himself with the wealthy toys of some of the other ‘Golden Greeks’ – yachts, fancy cars or a private jet. A picture of normality, he was never recognised in the street. Despite the international scope of his business, he prized home and family life, which he enjoyed after his marriage to Melpo Pateras, daughter of another shipping family and with whom he had three children.