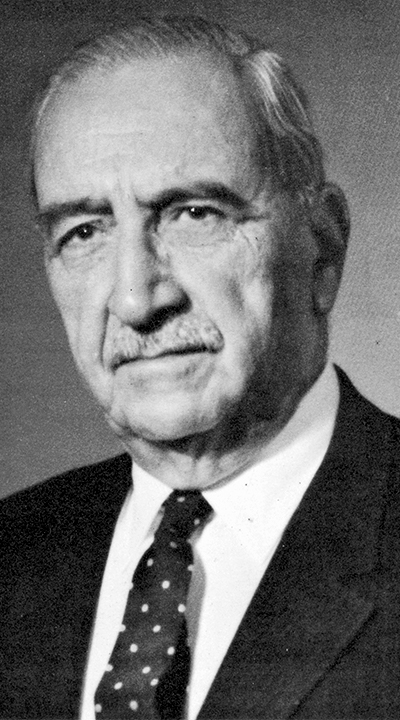

PERICLES Callimanopulos dedicated most of his career to establishing an international liner company that would also serve the Greek economy. His steady quest to achieve this vision makes him a unique figure in the annals of Greek shipping. He was born in Patras in 1892, into a family that only a few decades earlier had been prominent fighters in the Greek revolution against the Ottoman Empire. Courage and independence were also hallmarks of his shipping career.

Despite his studies in English, French and accounting, a scarcity of jobs in a desolate Greek economy just before the Balkan Wars forced the young Callimanopulos to emigrate to Egypt to find work after leaving school. A first job in Alexandria set him on an early career in ship agency work and he rose to a managerial position in the network of Koulis & Co., for which he worked in both Piraeus and Alexandria.

His professional career was interrupted by the First World War when he served in the Transportation Corps of the Greek army. After the war he opened his own office in Piraeus, working as a chartering broker as well as doing liner agency and coal trading. He was appointed agent of a German company serving regular routes between the eastern Mediterranean and northern Europe. But in spite of successful results, he was cast adrift when the company he represented joined a conference and appointed the consortium’s agents.

In 1924, he took his first step as a shipowner by purchasing a 34 year-old freighter, the first of several ships he would buy or partly-own over the next 10 years.

He launched Hellenic Lines in 1934 and the company established regular cargo services between the Black Sea, Mediterranean, London and Northern Europe as well as the Middle East.

By the outbreak of the Second World War, it was carrying a large share of Greek exports to Europe, but the fleet was diverted to the Atlantic convoys and seven of its eight owned vessels were lost during the war. The company was faced with the enormous task of rebuilding itself after the war.

Callimanopulos had operated the company from Greece during the war having chosen to stay in Greece and having with his family survived the German occupation of Greece and all the risks and hardships that entailed. But in 1945 he moved to New York with his family. Reflecting the company’s status and its losses during the conflict, Hellenic received five of the six Liberty ships that it requested out of the 100war-surplus vessels that were allotted to Greek shipowners.

Thereafter, between 1949 and 1951, he managed to acquire another five Liberty ships secondhand as well as three tankers for a new tramp operation that promised much better financial returns. One shrewd Greek shipping personality of the post-war period considered that if Callimanopulos had stuck to the easier tramping type of shipping his abilities would have made him more financially successful than Onassis and Niarchos.

However he made the conscious decision to give most of his attention to rebuilding Hellenic Lines’ regular services in the interests of serving Greece’s import and export needs. All tramping activities were abandoned and thereafter he dedicated all his energies and financial resources to his liner company.

He renewed Hellenic Lines’ regular service from the UK continent to and from the Eastern Mediterranean.

In 1946, Hellenic had offered a joint service with States Marine Corporation, trading as American Hellenic Lines, but this terminated the next year. Hellenic continued an independent service from the US to the Mediterranean. But the company faced huge difficulties in obtaining a share of the post-war supply shipments to Europe that were transported primarily by American steamers.

In rededicating himself during the 1950s to the tougher path of establishing his liner service, Callimanopulos extended Hellenic’s services from North America to the Middle East and Indian subcontinent. In Europe, though, Hellenic was barred from the conferences that controlled the trades. The company’s Greek flag fleet received little encouragement from the Greek government and frequently had to watch as non-Greek companies with the support of their governments carried the lion’s share of Greek trade.

A first generation of new freighters built for Hellenic in the UK and Japan was delivered between 1955 and 1957.

The line was further expanded in the 1960s with secondhand acquisitions and more newbuildings ordered in Germany and Japan. As the fleet grew so did the infrastructure.

In 1962, for example, the company expanded with the acquisition of a pier and warehouses in the port of New York. In addition to its main offices in New York, Greece and London, where it was represented by an affiliate, Fenton Steamship, Hellenic established subsidiaries and offices in various other ports. Among the most important were subsidiaries in Hamburg and Istanbul, and a significant office in New Orleans.

By 1968 Hellenic was operating a dozen international lines. A number of these ran from the USA and others from Europe to and fro the Mediterranean, Red Sea, Arabian Gulf, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Burma, and South Africa. About 40 ships were engaged in the company’s network, of which 36 liners were owned.

Yet everyday operating on many of the routes to and from Europe remained a battle as Hellenic had to compete as an outsider against closed conferences. It was a constant source of frustration for the shipowner that the Greek government did nothing to help its major carrier when the company was continuously suffering from what Callimanopulos himself called the “medieval practices” of rivals that wanted to shut him out of the business. In the last chapter of his career he lobbied the United Nations for reform of the closed conference system.

Condemned to operate as an outsider on key trades, Hellenic nevertheless built up a large share of the market on its routes.

Undaunted, at the age of 76, Callimanopulos embarked on a huge project to renew the fleet with modern vessel types. In the early 1970s, six modern multipurpose vessels, with holds configured for containers, were delivered by Oy Wärtsilä’s Turku Shipyard in Finland. Hellenic also supported its national shipbuilding industry, with another six SD-14 type liners built at Hellenic Shipyards.

In 1978 another step towards containerisation was taken with delivery of three large newly built ro-ro container vessels from Japan’s Sasebo shipyard, for the company’s US to Middle East service.

An extraordinary 68-year career in shipping came to an end on September 20, 1979 when Callimanopulos passed away at his office.

After Callimanopulos’ death it fell to son Gregory, who had independently established his own successful tramp shipping business out of New York, to take the company’s reins and continue the necessary modernisation of Hellenic Lines’ services with a major program to acquire and convert containerships. However, this coincided with a worldwide shipping slump and, unlike some major carriers in the liner trades, Hellenic found neither cooperation from its bankers nor support from its own government to ensure its survival.

Hellenic Lines, which was wound up in 1985, remains the only example in Greek shipping of a major liner operator.

Callimanopulos’ interest in containerisation, however, can be seen as a forerunner of a rising interest in containerships among contemporary Greek tramp shipowners.

Despite the lack of official support showed to Hellenic Lines in his lifetime, Callimanopulos’ stature was such that he was showered with recognition by Greece and other countries.

In 1952 he was awarded the Phoenix Gold Cross by King Paul for launching regular shipping connections of strategic benefit to Greece. In 1955 he was decorated with the Cross of the Royal Order of George I for services to Greek shipping. In 1957, the badge of the Grand Commander of the Royal Order followed.

In 1959 Callimanopulos was given the key to the city of New Orleans recognising Hellenic Lines’ extensive use of the port of New Orleans. In 1960 he was presented with the Naval Gold Medal from the Greek consulate in New York. Decorations in the 1970s included Italian medals for the development of Trieste and services to East and South Africa, and Belgium’s Knight of the Order of Leopold.

Although not from a seafaring background, Callimanopulos was a strong believer in Greek crews and was seen as a father-figure by many of his seafarers. All Hellenic ships flew the Greek flag and were manned completely by Greek seafarers. Of the 69 vessels he owned in his career 31 were newbuildings ordered by Hellenic over a period of 20 years.

He was a longstanding board-member of the Union of Greek Shipowners having first been elected in 1927 and having served a number of terms spanning a total of almost 45 years.